Fuel Poverty Strategy and action plan (draft)

Published April 2021 An accessible document from southtyneside.gov.uk

Purpose of the Fuel Poverty Strategy

The purpose of this strategy is to highlight the issue of fuel poverty and its impact on residents in South Tyneside, plus identify actions to tackle fuel poverty in the borough. This Strategy covers homes in the owner occupied, privately rented and socially rented sectors in South Tyneside.

| Owner occupied | Privately rented | Rented from either the Council or Registered Providers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 58% | 12% | 30% | 100% |

Table 1 – A table showing stock by tenure in South Tyneside (taken from 2019 data tables published by the Office for National Statistics - the number and percentage of dwellings by tenure, for local authorities in England and Wales, using an alternative method).

This Strategy will cover a 5-year period from 2022-2023 to 2026-2027. The accompanying action plan will be regularly monitored and evaluated by the Housing Strategy Team.

This Strategy was developed following extensive consultation across the Council, South Tyneside Homes and we will consult with stakeholders including:

- Age Concern Tyneside South

- AgilityEco

- Apna Ghar

- Bliss=Ability

- Citizens Advice Bureau

- First Contact Clinical

- Inspire South Tyneside

- Local Energy Advice Partnership

- Media Savvy

- Mental Health Concern

- National Energy Action

- NHS South Tyneside Clinical Commissioning Group

- North East Local Enterprise Partnership

- Women’s Health in South Tyneside

- Your Voice Counts

Aim of strategy

To reduce fuel poverty in South Tyneside and support vulnerable groups in tackling fuel poverty.

What is fuel poverty?

A household is considered to be fuel poor if it cannot afford to keep its home adequately warm at a reasonable cost, given its income. Fuel poverty is caused by a combination of low household income, high energy requirements and high energy costs, with energy-inefficient housing being a key driver.

Government has updated the way fuel poverty is measured.1 The updated measure, Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE), finds a household to be fuel poor if it:

- Has a residual income* below the poverty line† (after accounting for required fuel costs) and

- Lives in a home that has an energy efficiency rating below Band C.

*Residual income is defined as equivalised income after housing costs, tax and National Insurance. Equivalisation reflects that households have different spending requirements depending on who lives in the property.

†The poverty line (income poverty) is defined as an equivalised disposable income of less than 60% of the national median.

Government targets around tackling fuel poverty have been set to ensure:

- As many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable achieve a minimum energy efficiency rating of Band C, by 20302.

- Fuel poor homes are upgraded to Band D by 20253.

- All homes are upgraded by 2035 to EPC band C where practical, cost-effective and affordable4. ††

††The Climate Change Committee has recommended that all rented homes meet EPC band C by 2028. The Government published proposals5 in September 2020 to require all private rented homes to get to EPC C by 2028. This would apply to all new lettings from 2025.

These targets are based on Energy Performance Certificates for fuel poor homes rather than a specific fuel poverty level. An Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) is a rating of how energy efficient a property is. The certificates are graded on a scale of A (most efficient) to G (least efficient). An EPC is a legal requirement when a property is bought, sold or rented.

The impact of fuel poverty

Tackling fuel poverty can have impacts on several policy areas. For example, cold homes can have negative impacts on both mental and physical health, potentially adding demand to the NHS and social care providers, plus directly contributing towards excess winter deaths.

Transforming the housing stock so that homes are warm, healthy and fit for the future will help protect the health of those most vulnerable and reduce the strain on our NHS, whilst complementing the approach to more preventative healthcare.

Health impacts of cold homes include increased risk of heart attack or stroke, respiratory illnesses, poor diet due to ‘eat or heat’ choices, mental health issues, and worsening or slow recovery from existing conditions.

Older people and people with certain health conditions, such as heart problems, asthma, depression or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, can see their symptoms improve or even have their life extended by living in a warmer home.

Tackling fuel poverty also helps to reduce carbon emissions and keeps household bills down.

In addition, living in a fuel poor household affects children’s wellbeing and life chances.

Research by Shelter6 found that that children in poor housing are at greater risk of:

- Severe ill-health, disability and mental health problems.

- Respiratory problems such as asthma, infections such as meningitis and tuberculosis, and slow growth, which is linked to later coronary heart disease.

- Absences from school.

Fuel poverty is linked to lower educational attainment and a greater likelihood of future unemployment, low-paid employment and poverty.

National Policy

This Strategy complements several national policies including:

- In 2014, the Government introduced a fuel poverty target for England to improve as many fuel poor homes as is reasonably practicable to a minimum energy efficiency rating of Band C, by the end of 2030. The 2015 Fuel Poverty Strategy7, “Cutting the Cost of Keeping Warm”, set out Government’s plan to meet this target. On 11 February 2021, the UK Government released an updated Fuel Poverty Strategy for England titled Sustainable Warmth: Protecting Vulnerable Households in England8. It sets out how the government will tackle fuel poverty, while at the same time decarbonising buildings, so that those in fuel poverty are not left behind on the move to net zero, and, where possible, can be some of the earliest to benefit.

- The Clean Growth Strategy9 sets out proposals for decarbonising all sectors of the UK economy through the 2020s, including tackling fuel poverty and improving the energy efficiency of homes.

- The Energy White Paper10 addresses the transformation of the UK’s energy system, promoting high-skilled jobs and clean, resilient economic growth, delivering net-zero emissions by 2050. It also commits to consulting on regulatory measures to improve the energy performance of owner-occupied homes. Government is consulting on how mortgage lenders could support homeowners in making these improvements.

- The government will change Building Regulations so that from 2025 the Future Homes Standard11 will deliver homes that are zero-carbon ready. Homes will be fitted with low carbon forms of heating. A full technical specification for the Future Homes Standard will be consulted on in 2023. Legislation will be introduced in 2024, ahead of implementation in 2025.

- The aim of the Future Buildings Standard12 is to further amend Building Regulations to improve the energy efficiency and sustainability of new and renovated buildings. It proposes to create a new requirement aimed at reducing the risk of overheating in homes, plus proposes more stringent requirements for ventilation and energy efficiency when existing homes are renovated or when doors, windows or heating appliances are replaced.

- The Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) are currently reviewing the Housing Health and Safety Rating System (HHSRS)13. It is the risk assessment tool used by local authorities to assess hazards in residential properties, including excess cold. The Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and MHCLG will work together to ensure the HHSRS review takes account of the most up to date evidence on cold homes and aligns with wider Government aims on energy efficiency and fuel poverty.

- Government is consulting on updating the domestic Minimum Energy Efficiency Standards (MEES) for landlords in the Private Rented Sector; including raising the minimum energy performance standard to Energy Performance Certificate (EPC) Band C14.

- The Climate Change Committee (who advise the Government on decarbonisation) said in their Net zero report that ‘addressing fuel poverty should continue to be a priority’15.

- The Commons Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy Committee’s report on Energy efficiency: building towards net zero16 provided some estimates of the impact of energy efficiency on various sectors:

- Energy savings: total energy use could be reduced by an estimated 25% by 2035 through cost-effective investments in energy efficiency and low carbon heat.

- Cutting energy bills: Energy efficiency measures have already saved households around £290 per year since 2008. Reducing total energy use by 25% by 2035 would result in average energy savings for consumers of roughly £270 per household per year.

- Jobs: Similar scenarios suggest that between 66,000 to 86,000 new jobs could be sustained annually across all UK regions.

- Economic Growth: This ‘cost-effective’ approach would require an estimated £85.2 billion investment but would deliver benefits (reduced energy use, reduced carbon emissions, improved air quality and comfort) totalling £92.7 billion - a net present value of £7.5 billion.

- Optimises infrastructure investment: Energy efficiency can prevent expensive investments in generation, transmission and distribution infrastructure and reduce reliance on fuel imports - with a present value of avoided electricity network investment of £4.3 billion.

- Competitiveness: The UK is a net exporter of insulation and energy efficiency retrofit goods and services.

- NHS savings: Reduced NHS costs of roughly £1.4 billion each year in England alone. The health service is estimated to save £0.42 for every £1 spent on retrofitting fuel poor homes.

- Air quality: The present value of avoided harm to health is calculated at £4.1 billion in accordance with HM Treasury guidance.

- Plan for Jobs17 - outlines how the government will boost job creation to secure economic recovery from coronavirus, including supporting and creating jobs that facilitate making homes greener, warmer and cheaper to heat.

- The ten-point plan for a green industrial revolution18 sets out the approach government will take to support green jobs and accelerate the nation’s path to net zero.

- The Social Housing White Paper19 includes discussion about improving energy efficiency, decarbonisation and the need to tackle fuel poverty. It announced a review of the Decent Homes Standard20. The review will consider how the standard can work to better support energy efficiency and the decarbonisation of social homes.

- The Conservative Party’s 2019 Manifesto21 included a commitment to help lower energy bills by investing in the energy efficiency of homes.

- Mitigating and adapting to climate change is expected to present economic challenges and opportunities as the UK seeks to pursue ‘green growth’. The Government sees green finance as central to this transition. This is discussed further in the Government’s 2019 Green Finance Strategy.22

- The Queen’s speech briefing document23 reiterated the commitment to ensuring lower energy bills by investing in the energy efficiency of homes.

- New guidance for landlords of Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMO) will be published to clarify when an EPC is required and when the Energy Efficiency (Private Rented Property) (England and Wales) Regulations 201524 apply to HMO.

- The House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee25 has said that the UK’s legally binding climate change targets will not be met without the near-complete elimination of greenhouse gas emissions from UK building stock by 2050. The retrofit of the existing housing sector needs much greater focus and is at risk of letting the rest of the economy down on decarbonisation. Several recommendations for policy changes are made including that the Government should bring forward the allocation of the £3.8bn of funding (Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund) pledged before the 2019 general election. This would deliver cost savings at scale. This funding should be frontloaded to reap the benefits of cumulative emissions savings towards net zero.

- In addition, a range of measures are currently available to help alleviate fuel poverty including:

- At the time of writing the government are operating a Green Homes Grant Local Authority Delivery (LAD) scheme; local authorities can bid for funding under this scheme to improve the energy efficiency of low-income households in their area.

- The Energy Company Obligation (ECO) is a government energy efficiency scheme to help reduce carbon emissions and tackle fuel poverty. The ECO3 scheme consists of one distinct obligation: The Home Heating Cost Reduction Obligation (HHCRO). In order to benefit from ECO residents must own their own home or have the permission of their landlord, including if their property is owned by a social housing provider or management company. ECO3 is focused on low-income, vulnerable and fuel poor households.

- The Social Housing Decarbonisation Fund (SHDF) covers a 10-year period and has been designed to improve the energy performance of social rented homes, on the pathway to Net Zero 2050. The SHDF aims to deliver warm, energy-efficient homes, reduce carbon emissions and fuel bills, tackle fuel poverty, and support green jobs. The SHDF supports the aims of the Prime Minister’s Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution.

- The Warm Homes Discount scheme. Under the scheme, medium and larger energy suppliers support people who are living in fuel poverty or a fuel poverty risk group. Some smaller suppliers also voluntarily participate in part of the scheme. The scheme targets fuel poor households, through a rebate of £140. The Energy White Paper commits to extending the scheme until at least 2025/26 and government will consult on reforms to the scheme to better target fuel poverty.

- The ten-point plan for a green industrial revolution announced the introduction of the Home Upgrade Grant. Government have committed £150 million to help some of the poorest homes become more energy efficient and cheaper to heat with low-carbon energy. The Home Upgrade Grant will support low-income households with upgrades to the worst-performing off-gas-grid homes in England. These upgrades will create warmer homes at lower cost and will support low-income families with the switch to low-carbon heating, contributing to both fuel poverty and net zero targets.

- BEIS Sustainable Warmth - Protecting Vulnerable Households in England February 2021 Return to text

- BEIS Sustainable Warmth - Protecting Vulnerable Households in England February 2021Return to text

- HM Government Cutting the cost of keeping warm: A fuel poverty strategy for England 2015.Return to text

- HM Government Clean Growth Strategy 2017.Return to text

- BEIS Improving the Energy Performance of Privately Rented Homes in England and Wales 2020Return to text

- Shelter Chance of a lifetime 2006Return to text

- HM Government Cutting the cost of keeping warm: A fuel poverty strategy for England 2015.Return to text

- BEIS Sustainable Warmth - Protecting Vulnerable Households in England February 2021Return to text

- HM Government Clean Growth Strategy 2017.Return to text

- HM Government Powering our net zero future 2020Return to text

- MHCLG Future Homes Standard 2021Return to text

- MHCLG The Future Buildings Standard 2021Return to text

- DCLG Housing, Health and Safety Rating System 2006Return to text

- BEIS Minimum Energy Efficiency Standard 2017Return to text

- Climate Change Committee Net Zero: The UK’s contribution to stopping global warming 2019Return to text

- BEIS Committee Energy efficiency: building towards net zero 2019Return to text

- HM Treasury Plan for Jobs 2020Return to text

- HM Government The Ten Point Plan for a Green Industrial Revolution 2020Return to text

- MHCLG The charter for social housing residents: social housing white paper 2020Return to text

- DCLG A Decent Home: Definition and guidance for implementation 2006Return to text

- The Conservative and Unionist Party Get Brexit Done Unleash Britain’s Potential 2019Return to text

- HM Government Green Finance Strategy 2019Return to text

- Prime Minister’s Office Queen's Speech December 2019: background briefing notes 2019Return to text

- HM Government Energy Efficiency (Private Rented Property) (England and Wales) Regulations 2015Return to text

- House of Commons Environmental Audit Committee Energy Efficiency of Existing Homes 2021Return to text

Fuel Poverty and South Tyneside

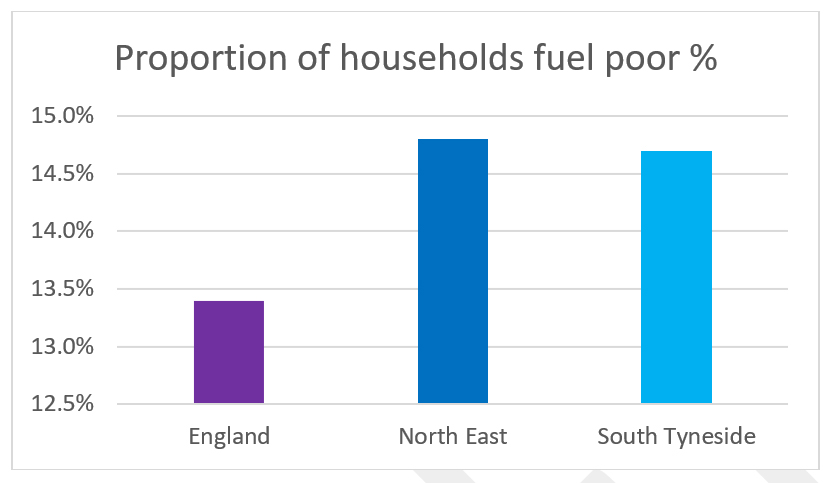

Fig.1 shows that the proportion of households in South Tyneside (14.7%) that are fuel poor is lower than the figure for the North East (14.8%) but higher than the proportion for England (13.4%).

In the latest year for which statistics are available, an estimated 3.18 million households in England were defined as fuel poor under the government’s fuel poverty definition. This was 13.4% of households. Within South Tyneside 10,457 (14.7%) of 70,930 households were estimated to be living in fuel poverty. This is higher than the national figure but lower than the North East proportion (14.8%).

Source: BEIS fuel poverty statistics

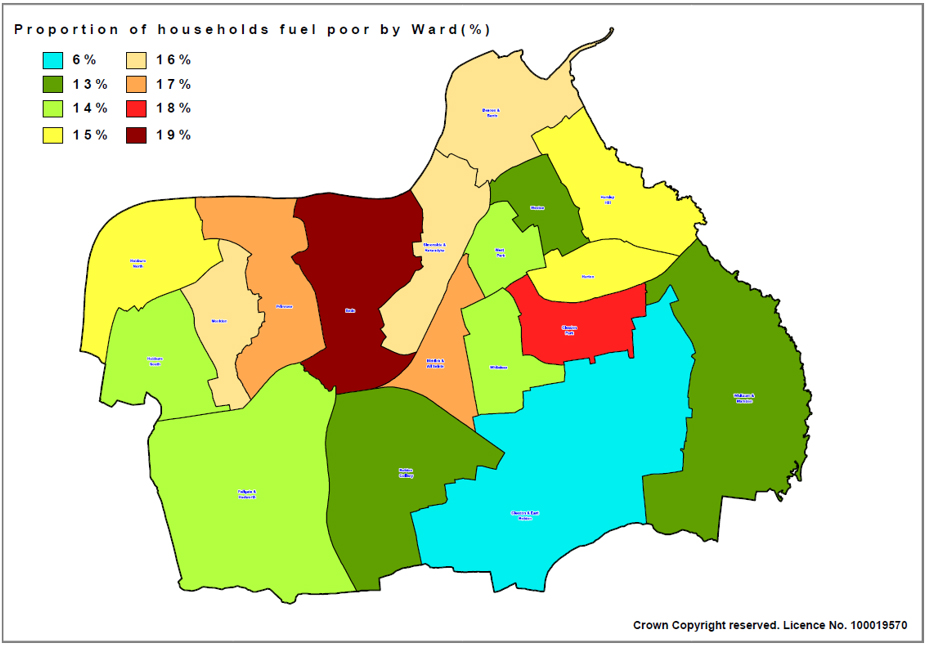

The map above (fig. 2) shows the proportion of households that are considered fuel poor by ward.

| Ward | Proportion of households fuel poor (%) |

|---|---|

| Beacon and Bents | 16 |

| Bede | 19 |

| Biddick and All Saints | 17 |

| Boldon Colliery | 13 |

| Cleadon and East Boldon | 7 |

| Cleadon Park | 18 |

| Fellgate and Hedworth | 14 |

| Harton | 15 |

| Hebburn North | 15 |

| Hebburn South | 14 |

| Horsley Hill | 15 |

| Monkton | 16 |

| Primrose | 17 |

| Simonside and Rekendyke | 16 |

| West Park | 14 |

| Westoe | 13 |

| Whitburn and Marsden | 13 |

| Whiteleas | 14 |

However, within South Tyneside there are several Lower Layer Super Output Areas containing a higher proportion of households that are fuel poor compared to the North East proportion.

Successful delivery of this strategy will complement other South Tyneside priorities, including those identified in:

- Asset Management Plan.

- Climate Change Strategy.

- Council Strategy.

- Economic Recovery Plan.

- Health and Wellbeing Strategy.

- Local Plan.

- Recovery and Renewal Deal for the North East.

- South Tyneside Homes Fuel Poverty Plan.

Reducing fuel poverty is a key part of South Tyneside’s and the North East’s economic recovery from the pandemic and will help generate growth and jobs by supporting a thriving post-pandemic economy and the UK’s sustainability and decarbonisation agendas.

Who do we need to target?

We know that some fuel poor households are more at risk from the impacts of living in a cold home than others, even if they are not necessarily the most severely fuel poor.

In tackling fuel poverty, low income, vulnerable residents that are living in homes rated below EPC Band C will be targeted. Based on information presented in the new Fuel Poverty Strategy for England, we consider the following low-income households to be particularly vulnerable if at least one member of the household is:

- 65 or older

- Younger than school age.

- Living with a long-term health condition which makes them more likely to spend most of their time at home, such as mobility conditions which further reduce ability to stay warm.

- Living with a long-term health condition which puts them at higher risk of experiencing cold-related illness – for example, a health condition which affects their breathing, heart or mental health.

We will use knowledge of areas of high fuel poverty, wider deprivation and poor housing, to target delivery at groups that are in most need.

Partnership approach

Local authorities have a central role to play in tackling issues relating to fuel poverty. However, South Tyneside Council cannot tackle fuel poverty alone and we will work in partnership to find solutions to the problem of fuel poverty. Partners include:

- Government bodies/departments.

- Local authority departments (e.g. Housing, Environmental Health).

- South Tyneside Homes and other registered providers in the borough.

- NHS, Public Health, Health and Wellbeing Board.

- Clinical Commissioning Group.

- Voluntary sector (e.g. Citizens Advice).

- Community groups/organisations.

- Utility companies.

- Businesses (e.g. contractors who install energy measures).

- Private Landlord Forums.

- Credit Unions/other regulated financial bodies.

Objectives

Fuel poverty is usually a result of three interacting factors; low household income, low energy efficiency standard of a property and high energy prices. Our focus is on supporting people to improve the energy efficiency of homes and providing advice and support. The three objectives are as follows:

- Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible.

- Improve the energy efficiency of homes.

- Reduce household energy consumption.

Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible

Low income affects the quality of housing you can afford. This increases the chances of an individual on a low-income being fuel poor.

Part of the long-term solution to fuel poverty lies in ensuring that families and individuals are as financially secure as possible and receiving all the benefits and tax credits to which they are entitled.

Reducing household expenditure and maximising incomes can lift households out of fuel poverty and reduce the risk of them falling into fuel poverty.

Residents will be supported to maximise their household income, manage their money and reduce excessive bills.

Improve the energy efficiency of homes

Improving the energy efficiency of homes is the most cost-effective and long-term solution to tackling fuel poverty. Improving home energy efficiency not only reduces the rate and risk of fuel poverty it can also:

- Reduce carbon emissions helping to meet the UK’s carbon reduction targets.

- Improve health and wellbeing.

- Reduce excess winter deaths.

- Lower NHS and social care costs.

- Generate economic growth.

Reduce household energy consumption

Energy consumption is determined mainly by the way people use energy in their home. These energy use behaviours are often habits which are hard to alter (e.g. leaving lights on and appliances on standby, or leaving electronic devices ‘plugged in’ and switched on at the wall, and not using heating and hot water controls to optimise efficiency). Behavioural change is the most effective and cheapest way to reduce energy consumption and carbon emissions.

Action Plan

Actions were developed for each objective:

- Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible

- Improve the energy efficiency of homes

- Reduce household energy consumption

| Objective | Action no. | Action | Timescales | Who will lead? | How will we measure success? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible | 1.1 | Identify potentially fuel poor households to target. | TBC | TBC | •Developed list of households in fuel poor areas of the borough that are vulnerable (also see action below under the next objective). • Monitor the location/number of households with prepayment meters. |

| 1. Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible | 1.2 | Engage registered providers in the borough and encourage incorporating energy efficiency/fuel poverty in the delivery of their money/debt/welfare advice services. | TBC | TBC | Evidence of promotion of services on registered providers websites/newsletters. |

| 1. Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible | 1.3 | Review the availability of income maximisation advice services across the borough. | TBC | TBC | •List the existing advice services available. •Develop a referral route for partner organisations to refer clients for support (including different options for residents e.g. 'face to face', online, telephone). • Increase awareness of organisations in the borough promoting income maximisation advice leading to increased referrals. |

| 1. Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible | 1.4 | Increase publicity around services offered to residents in the borough to maximise household incomes. | TBC | TBC | • Communications plan completed and implemented (e.g. publicising services offered such as budgeting advice, debt advice, employability advice) and by whom. • All front-line staff at South Tyneside Council (plus volunteers) and South Tyneside Homes are trained to spot signs of fuel poverty, how to report/refer it and how to successfully discuss it with residents. • Discuss Fuel Poverty with Health and Wellbeing Board/CCG and explore the possibility of all NHS staff visiting residents in their homes being trained to spot signs of fuel poverty, how to report/refer it and how to successfully discuss it with residents. • Increased demand for budgeting, debt advice and employability services. • A reduction in unemployment levels/improvement in education statistics/household income statistics/deprivation statistics/fuel poverty statistics. • Increased demand for welfare advice services e.g. benefit assessments to increase income. |

| 1. Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible | 1.5 | Explore opportunities with the CCG Social Prescribing Steering Group to target households with health problems (to both improve wellbeing and reduce household expenditure). | TBC | TBC | Social prescribing pilot commenced to potentially provide income maximisation advice for households with cold homes related health issues. |

| 1. Maximise household income and reduce household costs where possible | 1.6 | Explore establishing digital inclusion hub to support maximising household income, reducing household expenditure. | TBC | TBC | Potentially create hub to help tackle fuel poverty exacerbated by digital exclusion (potential link with Employability and Skills hub). |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.1 | Develop a central fuel poverty database/spreadsheet to hold all relevant energy data and encourage data sharing of implemented measures and EPC data. | TBC | TBC | • Central database/spreadsheet created and monitored - e.g. recording EPC ratings across all housing tenures. • Identify areas of the borough that are the most fuel poor compared to the regional average. •Baseline energy efficiency ratings for stock established and properties identified using available data sources. • Identify and target fuel poor households with a property rating of below EPC Band C for energy efficiency measures. • As many fuel poor homes as possible achieve EPC Band C by 2030. |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.2 | Create and distribute energy efficiency information to all potentially fuel poor homes to: • Increase awareness of SAP/EPC ratings and interventions available to improve energy efficiency. • Promote the extent of savings from energy efficiency measures, as well as assistance with identifying ways of financing upfront costs. Potentially offer or signpost to the following services: •Check availability of grants to improve heating and insulation in a home. • Support applying for grants for energy efficiency improvements. • Signpost towards installers/providers. |

TBC | TBC | • Energy efficiency information distributed. • Create a publicly available list of a summary of energy efficiency improvements and contacts. |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.3 | Increased engagement with owner occupiers and private landlords/their tenants about energy efficiency. | TBC | TBC | • No. of properties in owner-occupied/private rented sectors receiving energy efficiency advice/improvements/average EPC/SAP rating of homes increases. • Engage private landlords forum about energy efficiency issues. |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.4 | Improve energy efficiency of properties in social sector through increased engagement with registered providers | TBC | TBC | Average EPC/SAP rating of homes owned by registered providers increases. |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.5 | Explore opportunities for South Tyneside Homes to undertake energy efficiency improvements to private homes [e.g. if undertaking planned energy efficiency works (including window replacement) to properties, take advantage of economies of scale to offer the same service to neighbouring owners/landlords}. | TBC | TBC | • Opportunities discussed and plans developed/implemented if feasible. • Benefits of opportunities include additional income generated for housing and associated services. |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.6 | Liaise with planning department to ensure draft Local Plan is amended to discuss the importance of tackling fuel poverty/climate change to ensure energy efficiency standards in new build housing improves. | TBC | TBC | Ensure energy efficiency and fuel poverty are sufficiently highlighted in new Local Plan and during discussions to build new homes. |

| 2. Improve the energy efficiency of homes | 2.7 | Ensure practical support is available to older or disabled people, in the form of a 'handyperson' service (physical help to make energy savings changes e.g. draught proofing windows and doors). | TBC | TBC | Handyperson service pilot established. |

| 3. Reduce household energy consumption | 3.1 | Provide/signpost residents to free and impartial energy efficiency advice and information to educate households on the impact of lifestyle/behaviour/attitude changes in reducing their energy consumption and bills. | TBC | TBC | • Establish referral route to receive free and impartial energy efficiency advice and information. • Targeted publicity campaign about the importance of energy efficiency, behaviour change and associated cost savings. |

| 3. Reduce household energy consumption | 3.2 | Encourage behavioural change by promoting the benefits of installing Smart Meters. | TBC | TBC | Targeted publicity campaign about the benefits of installing Smart meters, behaviour change and cost savings. |

| 3. Reduce household energy consumption | 3.3 | Explore options for helping new South Tyneside Homes tenants get onto cheaper gas and electricity tariffs. | TBC | TBC | Void property energy management and tenant switching services potentially established to ensure the cheapest gas and electric tariffs for new South Tyneside Homes residents. |

| 3. Reduce household energy consumption | 3.4 | Encourage registered providers to work together to promote behaviour change | TBC | TBC | Evidence of registered providers working together to tackle fuel poverty. |